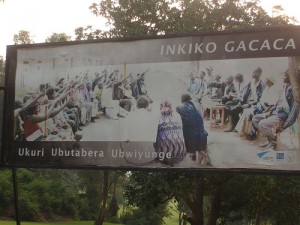

Rwandan billboard advertising the Gacaca courts - which are slated to close at the end of this month

On February 24 this year, Béatrice Nirere was sentenced by a Gacaca court to life imprisonment with “special conditions” (isolation) for her involvement in planning the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi population in Rwanda. This week, I sat in an over-crowded stifling room (despite glassless windows, no fresh air made it through due to the number of people cramming to see inside) as her case was considered for review.

I had gone to the Gacaca Court of Kanombe District in Kigali with a recent college graduate by the name of Valence. He was in Uganda during the genocide, but returned in 2004 to study law in Rwanda with the aim of working in human rights. As we walked up to the drab concrete building that serves as the office/ hall for the sector, a crowd was milling around, and most of them seemed to know my companion. In a hodge-podge of Kinyarwanda, French and English I met a number of Valence’s friends – current students and recent graduates. I asked each of them why they were interested in today’s Gacaca court. The final answer was one I was unprepared for: “They’re judging my Mum.” Valence slapped his friend on the back “Good luck man.”

Soon a mini-bus arrived with the six, perfectly gender-balanced, Inyangamugayo (literally, “persons of integrity”) who were to judge the appeal. With sashes in the colours of the Rwandan flag, they made their way to the long wooden table at the front of the room and began the usual courtroom formalities of identifying who was present. It’s a routine I have sat through countless times in the pristine air-conditioned courtrooms of the ICC and the ICTY in The Hague. But the familiarity of the process only served to heighten the differences in environment.

The differences weren’t in just the physical surroundings either. The most striking aspect was the size and attentiveness of the audience. While the first few days of the Milosevic trial, or the ICC’s first case against Thomas Lubanga, attracted huge audiences of journalists and diplomats, the remaining weeks and months were performed in front an ever-dwindling crowd – mostly tourists coming to see what “international justice” looked like in action. The Gacaca court was very different. I later found out that most of those who managed to get seats inside the room were victims of the genocide, or former neighbors of the accused. I was the only foreigner present.

In the front row, alongside Nirere, were three men – all in the same absurd pink pajama outfit distributed to the inmates of Rwanda’s prisons. The presiding judge had these men, along with another ten men and women, moved into isolation as the appeal commenced to be sure the evidence they were to give would not be contaminated by the testimony of the others. With the formalities out of the way, Nirere took the floor to begin presenting her reasons for appeal.

Nirere had been the sous Préfet of Byumba before and during the genocide. However as the killings started in April 1994, she left Byumba to stay with her children who were studying in Kigali. She stood in front of the video camera recording the session to explain that no one has ever actually provided evidence that she did attend any of the planning meetings for the genocide and that, in essence, the entire case against her was based on hearsay.

Instinctively I found it hard to believe that this woman, who was a proudly confirmed member of the now-outlawed Hutu Power party, the MRND (Mouvement Républicain National pour la Démocratie et le Développement), could be free from complicity in the planning of the genocide orchestrated by those in her ranks. But as the day progressed it seems that from a strictly legal perspective, she had a point. Anything other than hearsay evidence was so thin on the ground I wondered how she could have ever been lawfully charged with anything, let alone sentenced to what is now the most severe punishment in Rwanda following the abolition of the death penalty.

Virtually without fail, each witness brought into the room professed not to have known Nirere before or during the genocide. The first words to come out of the mouths of five consecutive witnesses were: “I have nothing to say. I didn’t know this woman.” The consistency of their denials raised a red flag for me. And I was not alone. “Witnesses are scared in this country” commented one of Valence’s friends after the session finished for the day. “They know that any night someone can come into their house and kill them. It has happened.”

The panel of Inyangamugayo persisted through the denials, asking probing questions that led some witnesses to backtrack and say that they did perhaps know her, but they never actually saw her attend any meeting. They then came back to Nirere, asking her what steps, if any, she had taken to prevent the genocide. “When the weather is changing, people start looking for an umbrella” explained the presiding judge. “Even if you weren’t at any planning meeting, you would have heard something was going to happen – what steps did you take to stop it?” he asked. “I don’t know what to tell you. I didn’t know a genocide was being prepared. I was surprised like any other citizen” Nirere replied, implausibly.

The hearing continued for six hours straight – none of this two-hour lunch break business that judges in The Hague are accustomed to. There have been mixed reports of the quality (and corruptibility) of the Inyangamugayo since the Gacaca process was established. But the six that were before me were miles ahead of most judges that I have come across in the international system with respect to their ability to manage a complex courtroom, handle hostile witnesses, and connect the dots between disparate pieces of incoming information. Best of all, they were 100% focused on the task before them – and with the accused and her supporters sitting right beside survivors of the genocide, their professionalism was reassuring.

The ICC is the first of the international criminal law forums to have a mandated role for victims in the trial process. The victim participation elements in the Rome Statute are considered revolutionary. And in many ways they are. But the victims’ participation in the courtroom dialogue is mediated through their legal representatives. And while many of the victim’s counsel are skilled at bringing the reality of their client’s experiences into the courtroom, it is nothing like the direct, unfiltered participation of a Gacaca courtroom.

On top of the tension generated by victims directly confronting alleged perpetrators, there is the unpredictability of “audience participation.” In some cases audience members had information to provide that was relevant to the case. But oftentimes, the opening that was offered to questions from the house was used to present an emotional monologue on what the speaker experienced during the genocide.

Once everyone who wanted to speak had spoken, the Inyangamugayo broke for deliberations. Valence and I headed to the kiosk across the road to get some much-needed water, and then came back to the crowd waiting for a decision.

An older man I got talking to, Ephrem, started telling me how he was in Nairobi when the genocide started, but his wife and children had been stranded here. By the time he was able to get back into Rwanda to look for them, he was expecting that they had all been killed. He was almost right. His wife, remarkably, survived a massacre in a church – one of only two to make it out alive. He said she covered herself with the blood of a dead baby and lay still among the corpses until the Interahamwe left. He found her in a hospital – one arm hacked off by a machete.

In the middle of this conversation, one of the pajama-clad men walked up and shook Ephrem’s hand. “This used to be my neighbor” Ephrem explained cheerfully. He introduced me and the prisoner-in-pink offered his hand. I reciprocated, trying not to look as awkward as I felt. “Here’s my wife, you must meet her!” said Ephrem as his former neighbor left us.

Half an hour later, the Inyangamugayo filed back in and the rest of the crowd jostled for the prized indoor seating, then sat waiting expectantly for the result. We were to be disappointed. The audience stood as the presiding judge began to speak. They wanted to hear from more witnesses before reaching a decision, he said. The hearing would continue tomorrow.

Valence got talking to Nirere’s son as we left for the day. He seemed to feel it had gone well. “Perhaps things are going to be okay” he said, as we strolled out to catch a moto back into the center of town. I had to head to Goma the next morning; Valence has promised to call me with the final decision . . .

[…] leading to a sentence of life imprisonment with “special conditions” (isolation). As I commented, during the first day of the appeal the case against her consisted primarily of hearsay evidence, […]